Africa’s Tourism Boom and Nigeria’s Costly Absence

As Africa’s tourism sector rebounds with renewed confidence, a striking reality emerges from the latest continental rankings: Nigeria is missing from the list of Africa’s top tourism revenue earners. While countries such as Egypt, Morocco, and South Africa post billions of dollars in annual tourism receipts, Africa’s most populous nation—rich in culture, history, landscapes, and creative energy—remains conspicuously absent.

READ ALSO:Dangote Group Signs $400m Equipment Deal with XCMG to Accelerate Refinery Expansion

This omission is not accidental. It is structural.

The Leaders and the Gap Nigeria Must Confront

According to recent tourism revenue data, Egypt leads Africa with over $15 billion annually, followed by Morocco at more than $11 billion, and South Africa with about $6 billion. These countries have built coherent tourism ecosystems: strong branding, visitor-friendly infrastructure, consistent security messaging, and aggressive international promotion.

Nigeria, by contrast, has relied on potential without structure.

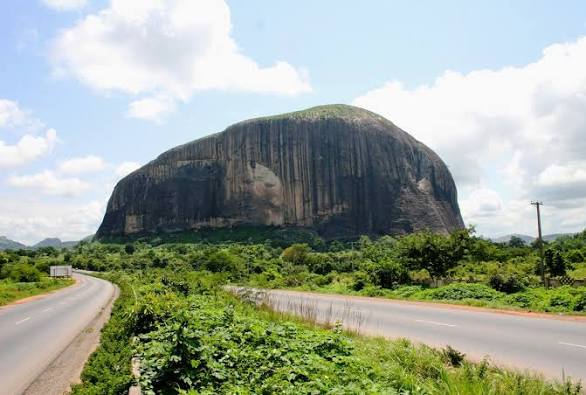

Despite its unrivalled cultural diversity, historic sites, festivals, cuisine, film industry, music exports, and natural attractions—from Obudu to Yankari, Osogbo to Badagry—Nigeria earns a fraction of what peer nations earn from tourism. The problem is not lack of assets; it is absence of strategy.

Why Nigeria Is Missing from the Tourism Earnings Table

First, tourism has never been treated as an economic priority. Unlike oil, banking, or telecommunications, tourism in Nigeria suffers from policy neglect, weak coordination, and fragmented ownership between federal, state, and local authorities.

Second, infrastructure gaps are crippling. Poor access roads to tourist sites, unreliable power supply, limited rail connectivity, weak signage, and inconsistent hospitality standards discourage both domestic and international visitors.

Third, security perception matters more than reality. Even when incidents are localised, Nigeria’s global image is often painted with a broad brush. Countries that dominate tourism revenue invest heavily in perception management, crisis communication, and tourist protection frameworks. Nigeria largely does not.

Third, security perception matters more than reality. Even when incidents are localised, Nigeria’s global image is often painted with a broad brush. Countries that dominate tourism revenue invest heavily in perception management, crisis communication, and tourist protection frameworks. Nigeria largely does not.

Fourth, visa and entry systems remain unfriendly. While Morocco and Egypt aggressively simplify visa processes and promote arrival-friendly policies, Nigeria’s travel bureaucracy remains cumbersome, discouraging casual and repeat tourism.

Finally, tourism has not been linked to Nigeria’s strongest cultural export: creativity. Nollywood, Afrobeats, fashion, literature, and festivals attract global attention, yet this cultural capital is rarely converted into tourism itineraries, heritage routes, or experiential travel packages.

This lot, the new helsman at the Nigeria Tourism Development Authority (NTDA), Dr. Ola Awakan must confront, alongside the Ministry of Arts, Culture, Tourism and Creative Economy, must confront.

Per-Visitor Revenue: Another Missed Opportunity

Beyond visitor numbers, Africa’s top tourism earners focus on how much each tourist spends. High-value experiences—heritage tours, eco-tourism, luxury safaris, gastronomy, festivals—drive per-visitor revenue upward.

Nigeria attracts visitors largely for business, family, or short stays, with limited tourism-oriented spending. There is little incentive structure to keep visitors longer, move them across regions, or immerse them in curated experiences that translate into revenue.

Tourism earnings are not about footfall alone—they are about design.

What Must Change from 2026 and Beyond

If Nigeria is to appear on this list in the coming years, the shift must be deliberate.

First, tourism must be reframed as an economic pillar, not a cultural afterthought. This means clear targets, budgetary backing, and measurable outcomes tied to employment, revenue, and foreign exchange.

Second, Nigeria needs a unified national tourism brand—one that moves beyond stereotypes and tells coherent stories about heritage, creativity, spirituality, and modern African life. Countries that lead in tourism sell narratives, not just destinations.

Third, creative industries must be integrated into tourism planning. Film locations, music festivals, literary trails, food tourism, fashion weeks, and cultural carnivals should be packaged and marketed internationally.

Fourth, state governments must compete cooperatively. Tourism is local, but branding is national. Incentives should reward states that invest in access, safety, and visitor experience.

Fifth, visa reform and digital entry systems are essential. Ease of entry is often the first signal of seriousness to global travellers.

Finally, tourism must be people-centred. Communities that host tourism must benefit directly—through jobs, infrastructure, and social investment—otherwise sustainability collapses.

The Opportunity Nigeria Is Yet to Claim

Tourism is one of the few sectors where Nigeria can earn foreign exchange without extraction, build jobs without heavy imports, and project soft power without coercion. Africa’s top earners have proven that this is possible.

Nigeria’s absence from the tourism revenue league is not a verdict—it is a warning.

As Africa positions itself as a global destination, 2026 must be the year Nigeria decides whether it wants to watch the tourism economy grow—or finally claim its place within it.

The assets are already here. What is missing is intention, coordination, and belief. And those, unlike oil, can be renewed.

This article was first published in the January edition of OurNigeria Magazine, released on January 31