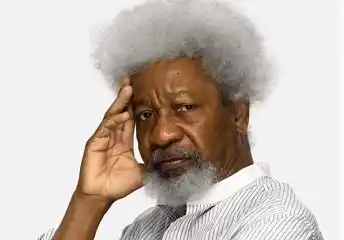

IN DEFENCE OF WOLE SOYINKA: Let the Man Rest, Let the Youth Rise

By Jerry Adesewo

The debate surrounding Wole Soyinka’s recent political positions — and the viral satirical dialogue imagined by Ope Banwo, “Who Are You, and What Have You Done With the Younger Wole Soyinka?” has reignited an old tension between reverence and rebellion, between hero worship and generational judgment. It has also forced a necessary conversation: at what point does the rebel earn his rest, and when does rest become retreat?

READ ALSO: Adventures With Nahla: A Heartfelt Tale of Courage, Faith and Growth

Banwo’s imagined confrontation between Soyinka at 50 and Soyinka at 90 is powerful, no doubt. It dramatizes the frustration of a generation raised on the ideals of defiance that Soyinka once embodied — a generation now bewildered by what appears to be his softening toward the very establishment he once challenged. It is theatre at its best — irony, symbolism, and provocation — the kind Soyinka himself might have written in his younger years. But beneath the satire lies a troubling undertone: a failure to understand that time, experience, and age do not erase conviction; they refine it.

Let us be clear — Wole Soyinka does not need defenders. The man who stared down dictators and lived to write about it hardly requires anyone to plead his case. Yet, as voices rise to question his consistency, it is important to pause and consider the possibility that the old lion has not lost his roar — he has merely learned when not to waste it.

The Burden of a Living Legend

Wole Soyinka is not just a writer; he is a living institution. For over six decades, he has stood at the intersection of literature, politics, and conscience — a bridge between art and action. From storming a radio station in 1965 to confronting successive military regimes, he earned his moral authority not by pontificating from comfort but by facing the consequences of dissent.

To expect that the same man, at 90, should still charge through the barricades with youthful fury is not only unrealistic — it is unfair. Activism, like art, evolves. The wisdom of age tempers the impulsiveness of youth. It does not mean capitulation; it means strategy. The Soyinka who sipped tea with those in power may be more deliberate, but he is not less dangerous to injustice.

There is, after all, a kind of protest that is louder in silence — a kind of defiance expressed in measured words rather than marching boots.

Between Fire and Wisdom

Banwo’s younger Soyinka accuses his older self of betrayal. Of trading fire for friendship, courage for convenience. But what if what we see as compromise is, in truth, the complexity of loyalty? What if Soyinka’s gestures toward people like Tinubu are not endorsements of power, but affirmations of personal history?

Must every relationship be filtered through the lens of political purity? Life, especially at ninety, is layered with nuance. Those who fight tyranny for a lifetime earn the right to draw personal lines of engagement. Friendship does not always mean complicity, just as silence does not always mean surrender.

Indeed, the younger Soyinka once said, “The man dies in all who keep silent in the face of tyranny.” But silence is not the only death; rigidity is another. The tragedy would be if Soyinka had refused to evolve, trapped forever in the costume of a perpetual rebel, unable to inhabit the wisdom of his own survival.

The Generation of Anger

When Soyinka calls today’s youth “children of anger,” it is easy to misread him as dismissive. Yet, perhaps he is issuing a caution, not a condemnation. The anger of a generation is legitimate — born of frustration, inequality, and betrayal. But anger alone is not activism. It must be guided by thought, by structure, by purpose.

The young Soyinka of Banwo’s imagination fought with words sharpened by intellect, not merely with rage. He did not abuse; he debated. He did not insult; he intervened. His defiance was creative, not destructive.

If the old man now warns of recklessness, maybe it is because he has seen revolutions devour their own children. Maybe his caution comes not from cowardice, but from the scars of experience.

For Art and for Posterity

I have said in some quarters where this conversation has come up: The loudness and activism of Wole Soyinka, often at the risk of his life and peace of his family, was his choice — a deeply personal, costly one. Why then should his “quiet” be our decision to make?

What did we do with the inspiration his youthful activism sparked in us? How well did we build on it to ensure the fire kept burning?

Let’s recall — this was the same Soyinka who, during the Civil War, risked imprisonment for standing by Biafra in the name of justice. How well did Nigeria reward that moral courage? Today, he is still attacked for a single comment that some interpret as being “against Biafra” or “against the Igbos.” It is a cruel irony — how a man can be hated for both standing with and standing apart.

Facts are sacred. Wole Soyinka cannot continue to fight our battles. Yes, he is 90+ and deserves his quiet, if he chooses to be. He has made his hay while his sun shone at 50, so he deserves his peace and quiet at 90.

The question then is: Has the man truly died in Wole Soyinka?

The answer will depend on who is answering — on where the “answeree” stands, or how he or she understands the question. But perhaps the wiser position is to let the man rest, while we begin to spend our own youth doing what he did in his. Just a fraction of it, even.

In Defence of Kongi

To defend Wole Soyinka is not to excuse his choices. It is to recognize that history is kinder to those who act than to those who only tweet. The man has lived the consequences of his convictions — prison, exile, exile again — while most of his critics have only lived in the comfort of commentary.

Let the young roar. Let the old reflect. Both are valid. But let us not mistake reflection for betrayal.

The younger Soyinka may accuse the elder of quietude, but it was that younger Soyinka who made possible the freedom to accuse at all.

In the end, perhaps the greatest tribute we can pay to Wole Soyinka is not to freeze him in the amber of his youth, but to allow him the full arc of his humanity — fire, flaw, and all.

Has the Man Died?

So, when people ask, “Has the man truly died in Wole Soyinka?” the answer depends on who is answering — and from where they stand. Those looking for a public fighter may say yes. Those reading his still-vibrant words, watching his legacy inspire new generations, know that the man lives — not in the streets, but in the spirit of every artist, thinker, and rebel who still believes words can change the world.

For the man who once wrote The Man Died, it is worth remembering: the man has not died — he has simply aged. And if you listen closely, beneath the weariness of his years, you might still hear the lion’s low growl rumbling through the pages of our conscience.

Let us, then, let the man rest — and begin to spend our youth doing even a fraction of what he did in his own time. Let us be the voices, the pens, the consciences of our era. Let us be restless for the right reasons.

Wole Soyinka’s work is ‘done’. Ours has barely begun.