1619: The Arrival That Changed History — Africans, Memory, and the Birth of American Slavery

1619: The Arrival That Changed History — Africans, Memory, and the Birth of American Slavery

1619: The Arrival That Changed History — Africans, Memory, and the Birth of American Slavery

In the late summer of 1619, a single event quietly unfolded on the shores of Point Comfort, near Jamestown in the English colony of Virginia—an event that would shape the social, economic, and moral foundations of what would later become the United States.

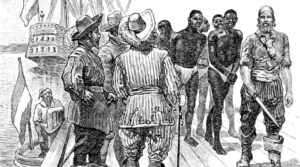

That year, the Portuguese slave ship São João Bautista was transporting hundreds of enslaved Africans from the region of present-day Angola, an area then dominated by the powerful African kingdoms of Ndongo and Kongo. The captives, torn from their families and communities, were forced across the Atlantic under brutal conditions. More than half are believed to have died during the voyage.

Before the ship could complete its journey, it was attacked by two English privateer vessels. The weakened São João Bautista was seized, and a portion of the surviving Africans were taken to Point Comfort. In a letter dated 1619, colonist John Rolfe informed Sir Edwin Sandys of the Virginia Company that a “Dutch man of war” had arrived carrying “20 and odd Negroes,” who were exchanged for food supplies.

Those individuals—men and women whose names and stories were largely erased from written records—are widely regarded as the first documented Africans brought to English North America. Their arrival marked a turning point. While systems of forced labor existed across Africa, Europe, and the Mediterranean for centuries, the transatlantic slave trade introduced something far more enduring: a racialized, hereditary system of bondage tied directly to economic profit.

At the time, the legal status of Africans in Virginia was not yet fully defined. Some historians note that early Africans may have been treated similarly to indentured servants. Yet the reality was harsh—many were compelled to labor in tobacco fields under coercive conditions, with little control over their lives. Over the decades that followed, colonial laws would harden, stripping Africans and their descendants of rights and permanently codifying slavery along racial lines.

By the 15th and 16th centuries, the transatlantic slave trade had become a vast commercial enterprise. Enslaved people were reduced to commodities—bought, sold, inherited, and exploited for economic gain. The humanity of millions was systematically denied, and the trauma of that system would echo across generations.

Yet the Africans who arrived in 1619 were not defined solely by their captivity. They came from diverse cultures, nations, and traditions. Though they carried little in material terms, they brought with them languages, spiritual beliefs, artistic expressions, agricultural knowledge, and deep memories of home. These elements became the foundation upon which African American culture would later grow.

In unfamiliar and often hostile surroundings, they drew upon their past to survive and adapt—blending African traditions with new realities, shaping music, religion, craftsmanship, and community life in ways that continue to influence American society today.

The arrival of the “20 and odd” Africans did more than supply labor to a struggling colony. It laid the groundwork for an institution that would endure for more than two centuries, profoundly shaping the nation’s history. Remembering 1619 is not only about acknowledging injustice—it is also about recognizing resilience, cultural endurance, and the enduring human spirit carried across the Atlantic against unimaginable odds.

1619: The Arrival That Changed History — Africans, Memory, and the Birth of American Slavery